Chapter 2

SITUATING SEARCH

Early on, the popular notion was that the Internet embodies a decentralized mode of provision; thus, no one entity could control it. In his widely cited book The Wealth of Networks Yochai Benkler celebrated the decentralized technical architecture of the Internet, posited how the networked information economy was different from the industrial economy of the pre-Internet era, and promoted a new mode of production outside the market economy.1 Yet, contrary to Benkler's and others’ early optimism—Robert McChesney refers to them as “Internet celebrants”2—capital has a firm grip on the Internet while democratic information-providing activities are, for the most part, marginalized. McChesney, Nikos Smyrnaio, Nick Srnicek, and others write that capitalism is the underlying principle in shaping the Internet, which is controlled by monopoly capital: A small number of large corporations controls the economy and sets prices through oligopolistic markets.3 The large corporations sustain their monopoly power and profit in the long run by creating and maintaining various barriers to entry such as economy of scale, mergers and acquisitions, intellectual property, and availability of financing.4 This monopoly capital approach captures the emergence of the tech giants and their increasing power over the Internet.

This chapter demonstrates, however, that Google's dominance of search doesn't mean that there is an absence of competition. The search engine industry competes not only in the United States but also on the regional and global levels in tandem with increasingly blurred sectoral boundaries that intensify intra-sector and inter-sector competition. In fact, Google's and other US tech companies’ global expansion has ignited current geopolitical conflicts attesting to the mesh between inter-state and inter-capitalist competition. Thus, the thesis of monopoly power alone is insufficient to explain the characteristics of the dynamics of the search engine industry. One must also address the underlying role of competition, which drives accumulation, expansion, and control of labor.

Anwar Shaikh argues that “the intensity of the competitive struggle does not depend on the number of firms, their scale, or the industry concentration ratio. Price-setting, cost-cutting, and technology variations are viewed as intrinsic to competition.”5 The competition of capital compels firms to do anything to cut costs and wages and drives new technical innovation in order to gain more market share and maximize profit.6 Richard Bryan notes, “Monopoly is the expression of a competitive process, not its negation.”7 Monopolistic tendencies and competition are linked dialectically in capitalism8 because they are exhibited in aggressive corporate strategies in what Kim Moody describes as “competitive war for profits.”9 The search industry, which is interwoven into and across economic sectors, needs to be situated within the dynamic between competition, ever-changing alliances, and the tendency toward concentration, rather than as a static condition.

With this as framework, this chapter first shows the scope of the search business which is expanding because search engine firms, in particular Google, are no longer merely trying to control this one domain. The most dynamic Internet sectors—search, social media, e-commerce, mobile, cloud—appear on the surface to be separate information spheres. Yet the major tech firms are all moving into each other's territories to compete, defend their existing profit centers, and carve out new profit sectors. In particular, the chapter shows how Google and its competitors are fiercely striving for mobile and cloud space. Furthermore, Google is engaged not only in the Internet sectors but also in the military, automobile, pharmaceutical, agricultural, education, and healthcare sectors and beyond. The Internet companies’ dynamics delineate their compulsion to capture at any cost any sectors they can wire and push to restructure into their profit domains with support from the capitalist state.

Second, this chapter illuminates the dynamics of the competition and expansion that are expressed in the infrastructure of control. It demonstrates how Google and its competitors Amazon, Facebook, Apple, and Microsoft are reconstituting domestic and transnational network infrastructures. As David Harvey points out, network infrastructure is a solution to the tension between fixed infrastructure and mobility of capital, data, goods, services, and labor to construct geographically dispersed markets. This is necessary in order to remove physical and spatial barriers to circulating capital.10 With regard to sectoral competition and geographical expansion, the tech firms contest as well as ally among each other and draw on regional capital to construct transnational network infrastructures. Specifically, the chapter discusses these firms’ major private infrastructure nodes—data centers, territorial fiber, and submarine cables—, which are supported by governments, directly and indirectly. Google is the nexus of these colossal global network infrastructures.

Dwayne Winseck argues that the US-based Internet giants don't control the myriad of layers of the Internet and its technical standards because the regional players from the EU and BRICS countries are increasingly playing a role in structuring global network infrastructure.11 This is true; however, the chapter focuses on the US Internet giants’ network infrastructures as part of their competitive and expansionary strategies as they try to outbid and outspend each other, investing massive amounts of capital in building private global networks to extend their Internet businesses and consume and control untapped or undertapped geographically dispersed parts of the world into their profit territories. The ascendance of the US-based Internet giants in network building is creating the geopolitical counterpressures from rivals that are discussed later, but this chapter expounds on the infrastructures that support ever-expanding Internet businesses and shows how they drive a new cycle of accumulation processes and open new “territories of profit,” to use Gary Fields's term.12

Defending Search

By situating itself between users and the Internet, the search engine industry established a critical point of control over information access. Tim Wu describes Google as controlling the “master switch” on the web in the way telephone operators at switchboards in the past made connections between parties, using the switch that can determine whom and what to connect.13 This rise of the search engines as an access point to the Internet has shifted the dynamics of and destabilized the information and communication sectors. The entire gamut of traditional media industries now has to rely on the search engine to reach potential audiences on the web. Google's ongoing disputes with publishers, newspapers, and the music and film industries over copyright issues and privacy, with the computer and mobile industries over patents and antitrust cases, and with the telecommunication industry over “net neutrality” around the world are demonstrating the battles between different units of capital as the information and communication sectors are being restructured. Drawn from the work of the economist Joseph Schumpeter, this is often described as creative destruction by technical innovation and creative entrepreneurship;14 however, this explanation overlooks the role of capital. In capitalist markets, entrepreneurs seek technical innovations not because they are entrepreneurial but because they have an imperative to maintain their market share to survive as capitalists.15 This involves the destruction of existing industries and the creation of new ones and the restructuring of old ones to renew capitalist accumulation.

In 2010 Google touted its success, saying that it “may be the only company in the world whose stated goal is to have users leave its website as quickly as possible.”16 Its chief executive at the time, Eric Schmidt, reiterated this point, once stating that Google would not be involved in the content business but, rather, would maintain itself as a “neutral platform for content and applications.”17 That perspective didn't last long, because the company soon pivoted. Google and other search engine firms are no longer merely pointing to information; rather, they own, manage, host, store, digitize, and duplicate information to extend their marketplaces and to pre-empt potential high-profit functions and services. Their businesses have been woven through the entire Internet value chain so as to control and extend profit territories encompassing the Internet backbone, hardware, software, content, services, and applications.

According to its 2021 annual report, Google's business is made up of two segments: services and cloud. Google Services is the largest division of its parent company Alphabet's business, which includes search and display advertising, the Android operating system platform, YouTube, consumer content delivered through Google Play, Enterprise, and Commerce, and hardware products.18 One of the company's major business focuses is still “access and technology to everyone.” Thus, to maintain its position of control as the main gateway to the Internet, Google has to compete with and block any companies that offer an access point to the Internet. In other words, the fight over search is not among horizontal search companies Microsoft Bing, Yahoo!, Yandex, and Baidu; rather, it is about control over the entire Internet value chain. Given that most of Google's revenue still comes from advertising, Google can't stay in its dominant position by merely being a superior search engine. If it is to secure its core territory of profit from advertising, Google has to control or at least have a hand in any route to the Internet by any means, including paying very large sums to its competitors. The company's attempts to prevent its rivals from accessing Internet entry points can be seen in the 2020 Department of Justice antitrust lawsuit against Google.19

The department's filing reveals that the main charge against Google was its control over “search access points.” The investigation showed that Google paid billions of dollars to device manufacturers Apple, LG, Motorola, and Samsung, to major US wireless carriers AT&T, T-Mobile, and Verizon, and to the Mozilla, Opera, and UCWeb browser developers to make Google their default search engine and restrict these companies from working with Google's competitors.20 In order to secure its position, Google has locked in its search distribution channels and paid between $8 billion and $12 billion per year to Apple alone, which is between 14 percent and 20 percent of Apple's annual profit and a third of Google's annual profit.21 The filing also reported that Google colluded with its major rival Facebook by manipulating its online advertising auction as a way to rein in its competitors. Besides forging a relationship with its competitors by leveraging its power, Google acquired hundreds of companies and filed for tens of thousands of patents. The largest number of patents in a single year that Google filed was 3,483 patents in 2012 to control the market and block future competition.22

On the one hand, Google's use of these control strategies, from locking up its competitors to alliances with its rivals to patents, is an exercise of its monopolistic search power, but on the other hand it is also a response to competition and to capitalism's imperative for expansion. As Rhys Jenkins writes, competition is a consequence of the self-expansion of capital.23 While Google's US search competitors Microsoft Bing and Yahoo! have made only little dents in the company's search market share, there is intense competition over hundreds of billions of dollars in the digital advertising market among other Internet companies and traditional media companies.

Facebook and Amazon are trailing closely behind Google's core business. In particular, the social media giant Facebook has been directly going after Google's main ad revenue sources. Facebook has been drawing on its massive user base and hoarding individual “intent data,” which is at the core of the search engine industry. It is challenging Google's most lucrative business as it offers information through Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger, all of which bypass and outflank Google. In response, Google launched its own—failed—social media platform, Google Plus (Google+). Despite facing uproar from both the public and lawmakers over its privacy practices, political ads, and cyber-currency business, Facebook still holds the second most visited website in the world after Google. The company generated $84.2 billion in ad revenues and drew more than ten million active advertisers across its services in 2020.24

Amazon, once Google's biggest advertiser, now threatens Google's advertising business. In 2021 Amazon generated $31.2 billion dollars in ad revenue,25 a distant third place behind Google and Facebook but surpassing 11 percent of the US digital ad business. Over the years, Amazon has become the primary search engine for e-commerce, which also cuts into Google's core function and pulls searchers away from Google's web properties. Ninety percent of Amazon's ad revenue came from sponsored products and brands on its e-commerce platform.26 If Google has built its advertising business by transforming the Internet into an ad platform, Amazon, the modern-day Sears catalog, has built its business by organizing the Internet as a vehicle for retail business. Since Google sells ads and Amazon sells products, they would seem to be in two different business sectors. Yet because the same companies that buy ads on Google are the companies the sell products on Amazon, if searchers go directly to Amazon and bypass Google to find products to purchase, then those companies pull or reduce ad spending on Google. For a decade Google made attempts to compete directly against Amazon by introducing the same-day delivery service Google Express, but these efforts haven't borne fruit. However, once again the company is trying to reboot its e-commerce to protect Google's core business as well as grab a controlling share of the almost $5 trillion e-commerce market by leveraging search, enticing sellers, and partnering with PayPal and Shopify.27

The real threat to Google's advertising business is coming from Amazon's accumulated data on over two hundred million active customers. They are not merely clickstream data, but detailed data on what people searched for, actually purchased, and paid for those purchases. This is still an undertapped gold mine for marketers. In his Cnet interview Jeff Lanctot, the chief media officer for Razorfish, the Seattle-based digital marketing agency, said, “Amazon understands better than anyone else what consumers want” because advertisers were eager to get their hands on Amazon's data.28 Some major marketing companies such as WPP PLC and Omnicom Group. Inc. have already begun to shift some of their advertising budgets from Google to Amazon.29 In 2019, according to the Wall Street Journal, WPP PLC, the world's largest ad buyer, spent $300 million on Amazon search ads in 2018, and its 75 percent share of Amazon's ad search spending was drawn from its Google search budget.30 In 2020 the car insurance company Geico was the largest buyer of Amazon ads, at, $11 million, followed by Comcast, P&G, Acura, and American Express.31 These increased revenues from ad sales mitigate Amazon's high capital costs and strategy of having a thin retail profit margin. Amazon's advertising has turned into a third major revenue source for the company after its e-commerce and cloud businesses.

From a different direction, the telecom giants pulled together to take on both Google and Facebook, both of whose ad businesses are built over the telecoms’ network infrastructures. The telecom companies controlled the pipes, but they still needed wider distribution channels, content, and ad technologies to challenge the Silicon Valley ad giants. Thus, there was a flurry of mergers and acquisitions of media companies by traditional telecom companies to allow them to move into online advertising.

Verizon bought AOL in 2015 and followed that up with the acquisition of the search engine Yahoo! in 2017, spending close to $10 billion, and created Verizon Media (formerly Oath, Inc.), a division of its media and online business, which integrated AOL and Yahoo!. Verizon Media made a multiyear deal with Google competitor Microsoft, as Microsoft's Bing Ads exclusively served search advertising platforms for Verizon Media properties including Aol.com, Yahoo.com, AOL Mail, Yahoo! Mail, Huffington Post, and TechCrunch. But the company struggled to draw advertisers and sold 90 percent of Verizon Media to the private equity firm Apollo Global Management for $5 billion because the company faced fierce competition against AT&T and T-Mobile concerning the 5G network. Soon Softbank scooped up Yahoo! Japan, paying for the perpetual rights to the brand and related technologies. Yahoo! Japan is still one of the most popular websites in Japan with more than 20 percent of the search market share in that country. Verizon has retreated from its online ad business for now.

Verizon rival AT&T also bulked up its advertising business. In 2018, AT&T acquired a Google competitor, the ad technology platform AppNexus, integrating its advertising and analytics businesses to make its television spots more enticing to advertisers. This was after AT&T's $85 billion acquisition of Time Warner, forming WarnerMedia, which includes CNN, HBO, TBS, TNT, Turner Classic Movies, Cartoon Network, and more. But AT&T didn't take over Time Warner merely to compete with its main rivals Comcast and Verizon; rather, it was to compete with Internet firms like Google, Facebook, Netflix, Amazon, and Apple. In 2015 AT&T had also bought satellite television provider DirecTV for $67 billion. This buying spree put AT&T seriously into debt, and the company's big bet on digital advertising didn't pay off quickly enough.32 A short three years later, in 2022, AT&T sold off Warner Media to Discovery, creating a new company called Warner Bros. Discovery, which is the second-largest standalone streaming behemoth, competing against Disney Plus, Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Google's YouTube. The competition over the capital-intensive streaming business is cutting into ad revenue as well. Meanwhile, the cable giant Comcast, which owns NBCUniversal, launched an ad-supported streaming service called Peacock to grow its targeted ad business. As the company continues to lose television subscribers, Comcast is bolstering its ad-supported Internet business.

Despite facing competition on multiple fronts, Google still reigns over its core advertising business so far. Yet its dominance in advertising is far from secure. In order to preemptively fend off its rivals and continue to grow, the company had to get a grip on mobile devices, on which a growing majority of people access the Internet today. The combination of mobility and Internet connectivity opened up new dimensions of commodification and commercialization for capital. This allowed capital to overcome physical obstacles to reach consumers 24/7 and to expand in space and time for capitalist production in previously untapped markets.

Going Mobile

In 2014 Google's chief business officer, Nikesh Arora stated, “The fundamental tenet is not to speak about mobile, mobile, mobile. It's really about living with users.”33 That is, the tenet of capital is not simply maintaining dominance over one's own domain; rather, the imperative is to expand by organizing and reorganizing every inch of peoples’ social lives into the profit domain. Given this expansionist compulsion, mobile Internet is a vital platform for capital, with the goal being to actually live with users and their always-on mobile devices, tied to an individual identification that can be tracked, and monitored, and commodified.

After acquiring the mobile-phone software start-up Android in 2008, Google launched its Android OS, followed closely by Apple's first mobile OS, in order to expand its ad business into the mobile marketplace, where Google competes with Apple. These firms took different routes in their accumulation and control strategies—Android was an open-source operating system while Apple was a closed system, a walled garden. Google's approach of allowing Android OS to be installed on as many phone models as possible meant that Samsung, LG, HTC, Sony, and Motorola all built Android-driven phones. Google CEO Eric Schmidt declared, “Android is by far the primary vehicle by which people are going to see smartphones…. Our goal is to reach everybody.”34 As the Department of Justice's filing in its antitrust suit reported, Google uses a version of open-source software but deploys various measures including anti-forking, preinstall, and revenue-sharing agreements to maintain control. It's “open source” but with rules by Google.

To compete against Google in the mobile space and diversify its revenue sources, Apple launched iAds, its mobile ad platform, in 2010, integrating advertisements into applications sold only in its iOS App Store. Apple tried hard to chip away at Google AdMob's lead in mobile advertising. Yet iAds failed and was discontinued. In particular, by exclusively serving iOS devices, Apple wasn't able to reach lucrative emerging markets where Android was dominant. While the company continues to seek alternative revenue sources such as subscription fees from Apple Music streaming, Apple Pay, and licensing—and while it faces a slowdown in device sales, a whopping 80 percent of its revenue—Apple hasn't fully abandoned its advertising business. It expanded its ad business via its app store. Armed with the knowledge that 70 percent of Apple store users use search to find apps, Apple moved into Google and Facebook territory and launched its mobile app search ads in 2016. In 2020 the Financial Times reported that Apple was developing its in-house search engine for displaying its own search results on iOS 14.35 And Apple's Siri already competes against Google Assistant, Amazon's Alexa, and Microsoft's Cortana. The development of its own general search engine and voice search is a direct attack on Google's core business, but it also gives Apple an alternative if regulators break up the lucrative agreement with Google.36

As mentioned in Chapter 1, Apple has increasingly positioned itself publicly as the vanguard of privacy, pushing privacy and security as a corporate strategy and a brand feature of its devices. If Google's accumulation strategy is surveillance, Apple's is exploiting privacy to curb its competition and regulatory pressure from the state. By deploying its new privacy policy, App Tracking Transparency, in April 2021 Apple asserted its privacy enforcement in its app store, forcing third-party app developers to ask users for permission to collect a unique identifier used by advertisers.37 App Tracking Transparency could negatively affect Google, Facebook, and in particular third-party ads companies that have less capital and infrastructure to cope with changes. Pushing privacy is a positive development, but Apple's move was far from altruistic. After it implemented App Tracking Transparency the company's ad revenues rose, and its own targeted search ads in the App Store increased.38

In the mobile advertising domain, one of Google's biggest competitors has been Facebook. Facebook released its own in-app advertising network, called Facebook Audience Network, in 2014, putting it into competition with Google's AdMob for mobile advertising. Facebook draws major advertisers such as Disney, Procter & Gamble, Walmart, and the New York Times with its billions of users.39 As of 2022 it is the second-largest player in the mobile space and has reached nearly 25 percent of mobile ad market share. In 2019 mobile ads accounted for 93 percent of Facebook's total ad revenue.40 The site's increasing power over the mobile space was threatening Google. To deflect competition and stymie Facebook's infringement on its core ads business, Google was willing to collude with Facebook and offer it preferential treatment in bidding for ad placement.41 A Texas-led antitrust case against Google revealed that the deal between the two companies concerned “header bidding,” which enabled online publishers to bypass Google's ad auction.42 Ad tech companies such as AppNexus, OpenX, MediaMath, and Pubmatic all built header bidding technologies to compete against Google's ad platform. By 2016 more than 70 percent of publishers used header bidding in an attempt to avoid Google. Google was worried that Facebook's ad service would adopt header bidding, which would significantly damage Google's ad revenue. In 2017 Facebook announced that it was working with ad tech companies and experimenting with the technology. However, the company soon changed its position and backed Google's ad platform after the secret deal with Google.

Google's competition in the mobile space does not come only from US companies. It also comes from its main Android manufacturers, Samsung and Huawei. Google's original strategy for its open-source OS was to rely on a number of different hardware companies to distribute Android and avoid letting one company get too big. But that strategy has faltered because Samsung has become a major seller of Android phones. Because of this development, Google could simply lose control over the mobile market if Samsung decides to use its own OS and leverage its market power against Google. Samsung once introduced its own mobile OS, Tizen, but failed to fully develop it. So far, Google has been able to maintain its control over device manufacturers by closely controlling its closed-source Google apps platform.43

The intensification of the geopolitical rivalry between the United States and China has also exposed Google's vulnerability. Amid the tensions between the two nations over trade and national security, the US government blacklisted Huawei on its Entity List,44 forcing Google to reluctantly revoke Huawei's Android license. This meant that Huawei was no longer able to access various Google services such as Gmail, YouTube, Google Maps, or the Google App store. As of now, Google has the upper hand and can exercise its power over the mobile market, while Huawei suffers without Google's apps. In the long run, however, Google could lose its grip on the mobile market given that Huawei was one of Google's major app distributors, selling more than two hundred million smartphones in 2018. Moreover, Huawei had a sizeable market outside the United States and had sufficient financial and technical capacity to build its own mobile OS system to move away from its reliance on Android.

Early on, Google and Huawei had preemptively pursued an alliance despite pressure from the Trump administration to reconsider the partnership on the basis of claims of a national security risk to the United States.45 This was not the first time Google had worked with Huawei, which was an important ally not only for Google's mobile business but also for its access to the unreached and potentially huge Chinese market. Even after Google was forced to pull Huawei's Android license, Google continued to try to persuade the US government that banning Huawei was bad for national security, arguing that it would be better for Huawei to be dependent on Google's Android OS than for there to be a Huawei-modified version of Android with a greater likelihood of being hacked.46 This is exactly what happened, as Huawei soon released its own OS, an open source–based fork of Android called Harmony OS. While it is still an open question whether Huawei will be able to bear the brunt of Google's ire without the support of Android in the global market, Google also clearly knows the risks and the strategic importance of mobile manufacturers for its business.

Google knew there was vulnerability in not being able to control the entire production process from design to manufacturing of its devices because the company sought full vertical integration. Google's acquisition in 2012 of Motorola Mobility, which made Android-based smartphones and tablets, for $12.5 billion was a way to prevent hardware manufacturers like Samsung from having too much control over Android.47 The acquisition did not turn out as Google had expected, and it sold Motorola Mobility to the Chinese firm Lenovo less than a year later—with Google keeping the majority of Motorola's patents. Google hasn't given up on manufacturing its own devices, however. It acquired HTC's smartphone design division, including “acqhiring” its two thousand engineers, for $1.1 billion and plans to control the entire design and manufacturing process, emulating Apple.48 The vertically integrated Google mobile phone Pixel launched in 2016. By manufacturing its own phone, Google can also mitigate the potential regulatory issues that could impact usage of its own services.

Google's phone gained less than 2 percent of the global market share, but it was part of a broader defensive and offensive accumulation and competition strategy. While Google tried to assert its power in the mobile space by managing to control the entire software and hardware production chain to secure its core business, the company needed to diversify its profit sources and bring its adjacent markets into the core. Cloud computing—on-demand availability of computer system resources, especially data storage and computing power, without direct active management by the user—was first brought into Google's profit orbit because it was capable of mass data processing, storage, and distribution. Vincent Mosco underscores the point that the evolution of cloud computing goes back to the 1950s and 1960s, when the concept of computer utility and information as a resource like water and electricity was first discussed; however, today it is driven by the goals of profit maximization and control, completely erasing the idea of computing as a public utility.49

The Cloud

The “cloud” was popularized after Google competitor Amazon created its first cloud service, called the Elastic Compute Cloud, in 2006; however, after the 2008 Great Recession, cloud computing was heavily promoted across the information industry as an efficiency and cost-cutting measure aided by the US government, which tried to boost the IT sectors in response to the crisis by spurring a new round of digitization of the economy. Corporate PR machines relentlessly promoted the message of cloud computing's prowess, brushing off labor, environmental, security, and privacy issues.50 By 2019 global IT spending had reached $3.76 trillion, with one of the key drivers of IT spending being the shift to the cloud across enterprises.51

For Google, cloud computing was not new territory per se. Google's most popular products, such as search, Gmail, Google Docs, Google Maps, Google Calendar, Google Now, and Google Drive, all run on Google's cloud infrastructure, where products are developed and data about users’ information-seeking activity are stored and managed. All along Google was running the biggest cloud-computing operation in the world—just with a different purpose. The company leverages its internal physical infrastructure to build out its cloud business, but Google's internal platform isn't easily configured for enterprise services as the company needed to bring the biggest spenders on IT—oil and gas companies, banks, governments, telecommunications firms, and healthcare companies—onto their cloud.

To entice corporate enterprises, Google tried to differentiate itself by bundling AI and machine-learning capabilities with its own Tenor Processing Unit chip for speed, along with developer tools. The company has also allied with Elon Musk's SpaceX, in which Google invested $900 million to install the space company's satellite Internet service, Starlink terminal, at Google's data centers around the world.52 Major corporations like Deutsche Bank, Ford Motor Company, the Mayo Clinic, and Univision have signed with Google cloud, but Google, with its mighty technical capacity, is still struggling to attract more large enterprises that are substantial revenue sources.

Microsoft and Amazon understand well the enterprise side of the cloud business; many enterprises have experimented with or are running apps on Amazon Web Services (AWS). While Google has wedged itself into the enterprise cloud market, Amazon has been working to cement its dominant position.

Despite Google's massive investment in cloud infrastructure, Amazon and Microsoft still lead the cloud market with over 50 percent market share combined.53 In 2006 Amazon launched its cloud computing platform AWS as a side project for its e-commerce, but AWS quickly turned into a major profit source, while its e-commerce business was in the red until 2017. Amazon sells its data storage and processing power to companies around the world. Fortune 500 companies including Apple, GE, Shell, Adobe, BMW, Netflix, and Pfizer avail themselves of AWS.

Microsoft's Azure cloud platform trails closely behind Amazon since the company transformed its Windows and PC business into one of the leading enterprise cloud providers in the world. As the global PC market waned, Microsoft quickly positioned itself as a cloud service provider. Leveraging its existing enterprise business, Microsoft made cloud its most important piece. The company supplies a range of services, including Microsoft 365 as apps, development platforms, and hybrid cloud services, which means consumers can combine cloud services and software.

The most lucrative market, the US government, is still up for grabs, however. Government patronage is vital to controlling the market. In 2021 the federal government spent a total of $8.2 billion by contracting out to private cloud services, an almost 20 percent increase over the previous year.54 All of the cloud giants have taken aim at the state, the largest organization in the enterprise market.

The US government was the main cheerleader in stimulating cloud computing and generating demand when corporations were hesitant to move their IT operations to the cloud. It has been facilitating the expansion of cloud computing by mandating the implementation of cloud computing for federal agencies. The Obama administration launched its “Cloud First Policy” to shift federal IT infrastructure into cloud computing under the premise of efficiency, flexibility and cost cutting.55 With its policy of IT modernization, the Trump administration continued to support the migration of federal government IT infrastructure to the cloud. In particular, the Department of Defense (DoD) and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) made strides toward enterprise cloud service as they increasingly deploy cloud computing on the battlefield and for cybersecurity. Under the umbrella of the Commercial Cloud Enterprise program the CIA also expanded its use of cloud services to power technologies for US intelligence. The result is what Mosco describes as the construction of the global surveillance state.56

In 2017 Google was awarded a DoD contract for Project Maven, which deployed AI on the battlefield.57 Google's work with DoD had received little attention until The Intercept and Gizmodo revealed the company's involvement in the military project.58 The revelation mobilized Google employees to protest against the military contract. This forced Google to drop the bid and pull out of Project Maven. For the moment, Google had withdrawn from its defense contract, but the question remained whether the company could afford to not work with DoD because its competitors were swiftly lining up for billions of dollars in government business.

After not renewing its contract with DoD, in 2018 Google CEO Sundar Pichai stated in a blog post, “We will continue our work with governments and the military in many other areas…. These collaborations are important, and we'll actively look for more ways to augment the critical work of these organizations and keep service members and civilians safe.”59 This statement suggested that future work with DoD hadn't been foreclosed after all. In 2020 Google's cloud division was awarded a new contract by DoD's Defense Innovation Unit to work on cybersecurity. The unit is the Pentagon's Silicon Valley outpost, established in 2015 to strengthen the existing ties between DoD and Silicon Valley. By working with the Defense Innovation Unit, Google signaled that the company had reinserted itself into the military-industrial complex. The United States spent $714 billion on defense in 2020; Google couldn't afford to lose this very lucrative market because Amazon and Microsoft have both become deeply involved in the business of war. In 2022 Google established a new division—Google Public Sector—aiming to bid on Pentagon and other government cloud contracts.

Amazon has already taken a significant share of the government cloud infrastructure market. The company has opened two dedicated secret cloud regions for the US government. In 2013 Amazon won a ten-year, $600 million contract with the CIA, unseating IBM, a long-time federal contractor. Unlike other contracts, which provide that its cloud resides inside Amazon's data center, the CIA contract required that cloud services be held within the CIA's data center—a completely separate, private cloud.60 This contract opened the door for Amazon to garner other major government contracts including one with US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. In 2014 Amazon pocketed about $200 million from the federal government, but by late 2019 the company had pulled in $2 billion from the CIA and other intelligence- and military-related agencies.61 Amazon is poised to be the leading federal government cloud contactor, but Microsoft is nipping at Amazon's heels.

Microsoft's winning the $10 billion, ten-year Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI) cloud contract in 2019 promised to further pave the way for Microsoft to be the forerunner in the military-information-industrial complex.62 But Amazon filed a lawsuit challenging the DoD's decision, arguing that JEDI's awarding process involved “clear deficiencies, errors, and unmistakable bias.”63 Amazon referred to former president Donald Trump's feud with Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos and the Washington Post (which is owned by Amazon) over the Post's critical coverage of the president. The president denounced the Post and Bezos and had considered intervening in the JEDI contract;64 Amazon argued that his bias had influenced DoD's decision. In 2021, under the Biden administration, DoD annulled the disputed contract with Microsoft and announced that a new multibillion-dollar program called Joint Warfighter Cloud Capability would replace JEDI. Defense stated that multiple vendors including Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Oracle, and IBM would be involved in the new project.65 This signals that DoD will prop up and stimulate the growth of the US cloud industry by enlisting the major tech companies and broadening the US military-industrial complex.

The JEDI contract was not Microsoft's only military contract; the company had long sought out lucrative military procurements. In 2019 the company won a five-year, $1.7 billion contract with seventeen intelligence agencies including DoD, CIA, the NSA, and the FBI.66 Microsoft was also awarded a $479 million contract with the US Army to provide HoloLens augmented reality headsets, which were intended for military training and combat.67 This brought a protest from Microsoft workers, who demanded that the company terminate the contract. The company defied the workers’ protests, stating, “We believe in the strong defense of the United States, and we want the people who defend it to have access to the nation's best technology, including from Microsoft.”68 The cloud war between Google, Amazon, and Microsoft is thus heating up, but they are certainly not the only players. Salesforce, IBM, Oracle, Rackspace, Virtustream, GoGrid, and Softlayer all have thrown their hats into the cloud ring.69

For years Google did not consider cloud computing part of its core business, but now the company is looking to this space as a major source of profit. Urs Hölzle, a senior vice president of technical infrastructure at Google, in a 2014 interview with Wired magazine, said that the revenue from the cloud could exceed the revenue that the company generates from online advertising.70 Google cloud hasn't exceeded ad revenue yet, but in order to seize the cloud market, the company seeks to “industrialize” the burgeoning multi-billion-dollar cybersecurity industry, which is predicated on network connectivity. The resulting battle between tech firms over the cloud is set to be huge and protracted and will give rise to conflict over controlling the Internet's infrastructure itself.

Infrastructure of Control

This battle to compete and control the Internet is manifested in the physical infrastructures of the Internet firms. Because Internet services hinge on networks, Google and its usual competitors have overseen a massive build-out of their global Internet infrastructures, ownership of which is strategically important to controlling traffic and speed and is the enabling condition for global expansion.

According to Google, from 2016 to 2018 the company spent $47 billion on capital expenditures.71 The majority of its capital investments went towards data centers, networking, and properties around the world, as Google operates in more than two hundred countries. In 2018 Google's capital expenditures reached $25.46 billion, almost double those of the previous year.72 The Wall Street Journal reported in 2022 that Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Facebook together have spent $90 billion on capital investments.73 US Internet companies are building out global Internet infrastructure because they have become its major investors, outpacing Internet backbone providers such as AT&T and Verizon in recent years. Although this infrastructure is invisible, Internet services rely on it to compute and transfer massive amounts of data back and forth. Led by Google, the Internet companies are racing to build major global network infrastructure nodes from data centers through the “middle mile” (territorial fiber and submarine cables that connect data centers) and the “last mile” connecting consumers and business users to this huge infrastructure of control.

Data Centers

Large-scale data centers, sometimes called “server farms” in an oddly quaint allusion to pre-industrial agrarian society, are centralized facilities that primarily contain large numbers of servers and computer equipment used for large quantities of data storage, processing, and high-speed telecommunications. For production of material goods, access to cheap labor has been one of the major criteria for companies in selecting their places of production, but data centers require only a small number of employees. The common characteristics of data center sites have so far been good fiber-optic infrastructure, cheap and reliable power sources for cooling and running servers, geographical diversity for redundancy, cheap land, locations close to markets, and government subsidies.74 The Internet giants are increasingly reshaping not only cyberspace but also the landscape as their hyper-mega data centers are increasingly occupying areas with some combinations of these components.

The tech journalist Steven Levy, describing Google's haphazard infrastructure, documented that initially Google rented only one collocation facility in Santa Clara, California, to house about three hundred servers.75 Soon, however, the company was purchasing entire buildings that were available at low cost (collocation sites) due to overexpansion during the dot-com era. Google began to design and build its own data centers, containing thousands of custom-built servers, and expanded its services and global market in response to competitive pressures. At first the company was highly secretive about the locations of its data centers and related technologies; a former employee called this Google's “Manhattan project.”76 Google eventually came clean to the public about them. This may seem as if the company had a change of heart and wanted to be more transparent about the data centers, but in reality it was more about Google's self-serving public relations onslaught. It wanted to show how its cloud infrastructure was superior to that of its competitors to secure future cloud clients.77 Now Google is building out its data centers around the globe to augment both its myriad services and its cloud business.

As of 2022, according to Google, the company has data centers in twenty-three locations around the globe—fifteen in the Americas (only one in South America), two in Asia, and six in Europe with hundreds of leased collocated data centers worldwide.78 Google's own data centers are still highly concentrated in the United States, where it receives 47 percent of its revenue;79 however, it has expanded in terms of scale and computational capacities domestically and internationally. Google currently has a data center in Singapore and in Taiwan and is adding a second one in Douliu, Taiwan, where multiple sea cables pass between the United States and Asia. The company also has one in Chile, and along with its centers in the Netherlands, Finland, Ireland, Denmark, and Sweden, it has acquired a site in Luxembourg and invested further in its existing Belgian site.

Google has also set its sights on the gulf region, a quickly emerging digital market. American corporations are not unfamiliar with doing business with Saudi Arabia, to which the United States sells billions in military arms every year. Silicon Valley firms have joined defense contractors in looking for potential business opportunities in this longtime US ally. In 2018 Google and Saudi Arabia's state-owned oil company, Aramco, discussed a partnership to build data centers.80 In the same year, the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, toured Silicon Valley and met with tech executives including Google CEO Sundar Pichai, Google co-founder Sergey Brin, Google VP of technical infrastructure Urs Hölzle, and Apple CEO Tim Cook.81

Amazon has also been in discussions with the Saudi government to offer its cloud service, but Amazon's expansion into Saudi Arabia was temporarily put on hold after Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi, a Washington Post journalist and critic of the Saudi government, was brutally killed by Saudi operatives inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in October 2018. Meanwhile, thirty-eight human rights groups demanded morality over profit and urged Google to withdraw from its Saudi cloud service contract because of the country's targeting of political dissidents.82 As of this writing Google has shown no signs of halting its plans to build the data centers, and its competitors are also expanding their cloud footprint in that region.

Google's search and cloud competitor Microsoft is also ramping up its computing power as the software giant accelerates its cloud business. In 2007 Microsoft built its first in-house data center in Quincy, Washington, which had a dependable and inexpensive supply of hydro-generated power available from the Columbia River. Since then, the company has invested more than $15 billion on infrastructure83 and currently spends about $1 billion per month on enterprise cloud computing infrastructure.84 Taking aim at the multi-billion-dollar government market, Microsoft built two data centers in undisclosed locations near Washington, DC, to exclusively host the government's classified data. Microsoft's cloud service is used across the federal government. Globally, Microsoft's network is composed of more than one hundred of its own and colocated data centers in places such as Abu Dhabi and Dubai, where Google, Amazon, and the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba already operate cloud services.85 In particular, Microsoft made an early move among US tech firms on the African continent, a key strategic growth region. There had been little hyper-scale data center presence in Africa due to the need for large-scale capital investment and lack of power supply; thus, the vast majority of African Internet content is stored outside the continent. In 2019 Microsoft opened a data center in Cape Town and one in Johannesburg for its Azure cloud service, beating out Amazon, which opened an AWS data center region in Cape Town in 2020 targeting African government agencies and enterprises.

Amazon, which generates more profit from its cloud business than from e-commerce, set up its first data center in 2006 in fiber-optic-rich Northern Virginia—where the US government in the late 1960s experimented with fiber optic networking—and has added eleven more data centers in Virginia since then.86 The exact number and location of the firm's data centers had never been revealed until 2018, when WikiLeaks published an internal Amazon document listing them.87 According to WikiLeaks, the document described as the Amazon Atlas indicated that the company has more than one hundred data centers, including colocations in fifteen cities across nine countries. Since then, Amazon has added at least three data centers in Bahrain, aiming for the Middle East region.88 According to the company, Amazon is offering its AWS cloud service across twenty-six regions, within which there are eighty-four separate locations that it refers to as “availability zones.” Each region is supposed to have between two and five availability zones, and each zone has one to eight data centers. Its cloud business has grown so fast that Amazon is now the fifth-largest software provider in the world, trailing just behind software companies Microsoft, IBM, Oracle, and SAP.89

Meanwhile, Facebook's capital expenditures continue to soar although the company has faced several legal issues over data privacy both in the United States and in Europe. So far, this hasn't slowed down Facebook's infrastructure expansion. The company opened its first server farm in Prineville, Oregon, in 2011, and since then has built eighteen data centers worldwide.90 This includes Facebook's first Asian data center in Singapore, an eleven-story, 1.8 million-square-foot building that is one of the largest data centers ever constructed. Singapore, also home to Google, Microsoft, and Amazon data centers, is a global financial hub situated in a prime geographical location as an entry into the Southeast Asian region.

Even Apple, which had relied on third-party cloud service providers such as Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, has now begun investing in its own data center infrastructure as it tries to reduce its reliance on the Internet cloud giants that are its competitors. Apple operates seven data centers in the United States including those in North Carolina, Oregon, Arizona, and Iowa.91 Outside the country, Apple opened its first data center in Guizhou, in southwest China, in 2021 to comply with data regulations instituted in the Chinese government's 2016 cybersecurity law,92 which require that Chinese consumer data be stored within the country. Its second Chinese data center is located in Ulanqab City, in northern China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, where data centers for China's domestic Internet giants Huawei and Alibaba also reside. For Apple, China—the world largest smartphone market—is one of its most strategically important markets.

These hyper data centers are all built with custom-designed software, servers, and chips as the companies try to better control critical computing power, as well as to reduce costs and reliance on middlemen. Google was the first company to design and make its own microchips; however, most of the major Internet firms including Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent have now followed Google's lead and are designing their own chips. This has become even more important as companies invest and compete in the burgeoning field of AI, which requires speed and massive computing power. These firms’ involvement in chip and hardware making undercuts such traditional chip makers as Cisco, Intel, HP, Qualcom, and Nvidia, threatening the existence of major networking equipment vendors.93 Given the scale of the hardware required for data centers, Internet firms have turned into big hardware manufacturing companies in their own right, independent of traditional chip industry and able to control their own supply chains.

Fiber

Data centers built with customized software and hardware do not stand alone. Geographically dispersed data centers are interconnected through the “middle mile,” which connects Internet providers via several means, for example, telephone lines, fiber optics, submarine cable systems, microwave, and radio spectrum. Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Facebook have all invested billions of dollars in middle-mile infrastructure to connect their data centers to circumvent the telecom companies, which own many of the Internet's pipes. Google is leading the pack. Google's Urs Hölzle asserted that “Google, for one, needs to double its transmission capacity every year to sustain the seamless appearance of its ‘Cloud 3.0’ computing.”94 Only a few companies have the financial resources, technological capability, and labor to build private network infrastructure; at the same time, there is a clear reason for wanting to control networks: the tech companies are competing over milliseconds of Internet traffic speed. Google calls this its “Gospel of Speed,” a rule that it requires all Google engineers and product managers to follow: “Don't launch features that slow us down.”95 According to Hölzle, a 400-millisecond delay would lead to a 0.44 percent drop in search volume,96 while Amazon found that 100 milliseconds in latency would cost 1 percent of its sales.97

Early on, Google understood that network infrastructure was critical for it to process the yottabytes of data that the company handles on a daily basis. Since 2005 it has been aggressively acquiring “dark fiber,” the unused underground cable left dormant by the dot-com crash of the late 1990s and early 2000s, or constructing private fiber-optic cables exclusively for its data center connectivity on land. In 2013 the Wall Street Journal reported that Google owned or controlled more than one hundred thousand miles of fiber-optic cable globally—compare that to Sprint, one of the largest global network operators, which controlled less than forty thousand miles at that time.98 Google's private backbone network has thousands of miles of fiber-optic cables that connect its data centers. Hölzle has said that Google built the world's largest network, delivering 25 percent to 30 percent of all Internet traffic.99 Facebook, Microsoft, and Amazon have also laid cables or bought dark fiber in addition to leasing network capacity. In 2018 Facebook revealed that it had deployed a new high-capacity underground cable in its Los Lunas, New Mexico, data center to diversify its flow of data routes.100 In fact, Facebook created a subsidiary called Middle Mile Infrastructure to sell its unused network capacity to local and regional telecoms, moving into the wholesale fiber market as it invested in fiber-optic routes with direct connectivity between its data centers in Ohio, Virginia, and North Carolina.101 In Indiana, the company has run fiber optic cables across the entire state and reaches to the border of Ohio.

Terrestrial fiber-optic cables are not sufficient to cover the global market, given that oceans cover 70 percent of the planet. The tech giants, therefore, have to go under water, resorting to a nineteenth-century technology—submarine cables—to reach and connect global markets. Submarine cables carry 99 percent of international Internet traffic and are the main conduits for intercontinental information flow including financial data. Submarine cables function as global economic nerve systems, illustrating the expansionary dynamism of digital capitalism. The Brussels-based Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication transmits forty-one million financial messages per day to more than eighty-three hundred banking and security institutions and corporate customers in more than 208 countries via submarine cables.102 Ten trillion dollars’ worth of global financial transactions go through the cables daily.103 The global economy thus hinges on the undersea network infrastructure that was initially developed and constructed by various colonial powers to connect and control their territories.104 Submarine cables are concentrated in the Atlantic Ocean, but there has been a rise in new submarine cable routes to Asia, Africa, and Latin America as Internet traffic rapidly expands in those regions. Over the period 2017–2022, the Asian Pacific and North American regions together were expected to account for about 70 percent of all traffic.105 The Middle East and Africa are closing this gap. They account for only 10 percent of total traffic, but they are the fastest-growing regions with a growth rate of 41 percent per year.106 In response to a compounded annual growth rate of 26 percent of global IP traffic overall from 2017 to 2022, new submarine cables were rapidly deployed to facilitate planetary digital capitalism.107

Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Facebook have emerged as major new players in the construction of submarine cables. This is hardly a surprise considering that these four companies consume more than half of submarine cable capacity.108 Less than a decade ago Internet firms used less than 10 percent of cable capacity; in 2020, they used 66 percent.109 The Internet giants have built out private submarine cables to better control their own traffic in terms of speed and have determined locations and routes to connect because they require expansive network capacity to coordinate data flows between their geographically dispersed global network of data centers.

By their very nature, submarine cables are capital-intensive infrastructure projects; thus, many companies have joined consortia comprised of groups of private firms to build cables and share network capacity. Roughly 90 percent of submarine cables are funded privately.110 Today's major involvement of private capital in the construction of submarine cables rather than state telecom carriers is the result of the deregulation that accompanied the ascendance of neoliberal telecommunication and Internet policy in the 1990s. After passing the Telecommunications Act of 1996 at home, the United States had spearheaded the effort to open telecom markets across the globe and pushed through the World Trade Organization's basic telecommunication agreement in 1997, which liberalized the global telecom industry.111 In addition to private capital, multilateral development banks such as the World Bank have also financed submarine cable projects, but this represents only 5 percent of submarine cable investment.

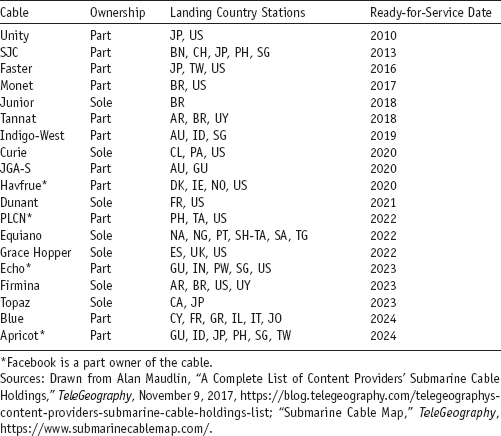

Recent years have seen a new trend in the undersea cable sector in which exclusive privately financed cables are on the rise, as content providers are increasingly participating in building out their own private cable networks. As of 2020 Google owned or had a stake in nineteen intercontinental submarine cables, six of them exclusively owned by Google, reaching from the United States to Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Africa, connecting to their data centers around the globe (see table 2.1).112

In 2018 Google began to lay out a trans-Atlantic cable connecting the United States and France. This was the first trans-Atlantic submarine cable to be built by a non-telecom company.113 The Dunant cable launched from Virginia Beach and landed at Saint-Hilaire-de-Riez. On the US side, it is close to northern Virginia in an area called “data center alley”—the world's densest intersection of fiber networks—where 70 percent of Internet traffic is routed.114 On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, the cable is close to Google's Belgian cloud region, where one of its hyper data centers resides. To cover the northern part of the Atlantic route, Google and Facebook, along with Irish firm Aqua Comms and the Norwegian firm Bulk Infrastructure, agreed to build the Havfrue cable between the United States and Scandinavia.115 The Havfrue cable, completed in 2020, connects New Jersey to the Jutland Peninsula of Denmark with branches to Ireland and Norway. It was the first submarine cable serving the United States and northern Europe to be built in the past twenty years.116 And the Havfrue extension, named AEC2, links New York and Dublin with routes to England and Denmark.117 In 2019 Amazon signed an agreement with Bulk Infrastructure for the use of Bulk's stake in the Havfrue trans-Atlantic cable.

Google's presence in the routes to Asia is undeniable, with eight cables—SJC, Unity, Faster, Pacific Light Cable Network (PLCN), Japan-Guam-Australia (JGA), Indigo, and Echo—covering most of the strategic hubs and key markets in Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Sydney, Singapore, Indonesia, and the Philippines. These trans-Pacific cables were built by consortia among regional and national telecom carriers including China Mobile. As the media scholar Nicole Starosielski has documented, the private consortium model doesn't necessarily transcend nation-states, because sources of investment and landing stations still need to be negotiated between nation-states.118 The state plays a vital role in controlling the data flow, so alliances between transnational capital and national interests are still required. These alliances, however, are not permanent. Thus, submarine cables as critical network infrastructure are geopolitical conflict points when transnational capital and national interests collide. Pacific Light Cable Network is a case in point.

Table 2.1. Google submarine cable holdings

Amid the tension between the United States and China, the PLCN cable—a 2016 joint venture with Google and Facebook, each having 20 percent ownership and the Chinese company China Soft Power Technology Holdings, a subsidiary of Pacific Light Data Communication, owning 60 percent—was put on hold.119 The PLCN was to be the first undersea cable with a direct connection between Hong Kong and Los Angeles, anticipating the growth of the region by further connecting Asia with its data centers in the United States. Hong Kong is the regional financial hub that links the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia as well as mainland China. The US Justice and Defense Departments opposed the construction of the cable for “national security” reasons in 2020, however, and asked the Federal Communications Commission to defer permission to land the cable in the United States.120 Google therefore had to revise its request to operate part of the PLCN cable. Its new plan would route data through Taiwan, where Google also has a data center. The FCC approved Google's revised request to operate a portion of the eight-thousand-mile PLCN, leaving the line between Hong Kong and mainland China as yet unbuilt.121 Due to this pressure from the US government, Google and Facebook have both withdrawn the cable line between Hong Kong and China for now.

In Latin America, Google has aggressively asserted its power, along with regional players such as Telefonica América Móvil and Telxius, linking together the region where the United States and its allies have suffocated the Bolivarian Revolution and brought in the International Monetary Fund to further push neoliberal policies in order to pry open the region for transnational capital.122 The neoliberal comeback drew billions of dollars into the burgeoning tech sectors in Latin America and, in particular, Brazil and Chile. In 2018, Google, Facebook, Telefónica Open Innovation, Qualcomm Ventures, and Telefónica OpenFuture formed the Latin American Tech Growth Coalition to attract private capital investment to the Latin American tech sector. Although it is a small amount compared to funds spent in Asia, North America, and Europe, capital investments in tech startups in Latin America grew more than fourfold, from $500 million in 2016 to a record high $2.6 billion in 2019.123

Google is seizing opportunities in this burgeoning market. The company has laid out four new cables—Monet, Tannat, Junior, and Curie—connecting the United States to Latin America and Africa. For Monet, Google was the main investor, teaming up with the Brazilian telecom giant Algar Telecom, the African telecommunications operator Angola Cable, and Uruguay's government-owned telecom company Antel to build a link between the United States and Brazil. The cable stretches from Boca Raton, Florida, to Fortaleza and Santos in Brazil This cable connects the growing markets of Latin America and Africa, so it is more of a long-term accumulation strategy for Google. Meanwhile, Google's first private cable, nicknamed Curie, connects the Equinix LA4 International Business Exchange data center in El Segundo, California, and the Valparaiso region of Chile, where Google's only data center in Latin America resides. This is the first submarine cable landing in Chile in two decades, and the cable has the capacity to branch out to Panama in the future.124

In search of every inch of land to absorb into its market as it races to new territories of profit, Google has reached to Cuba, the country that has been defying US capitalist imperialism and fighting for decades against US economic sanctions and embargoes.125 In 2014, with the goal of promoting a “free and open Internet,” Google chairman Eric Schmidt visited Cuba after touring North Korea and Myanmar with his delegation of top Google executives. Google intended to open up Cuba for transnational capital by facilitating the free flow of capital and the marketplace over the Internet. This didn't come out of a vacuum. Internet access was one of the central policies of the Obama administration in normalizing relations with Cuba. Soon after Schmidt's visit, Google was able to put its servers in the territory of Cuba to host content. The servers were part of Google's Global Cache service, which caches YouTube videos and other Google content to deliver them to local users faster. Cuba only connects to the global Internet through a cable called ALBA-1, short for Latin American Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America, running between Venezuela and Cuba. It was built in 2010 to bypass US-owned cables.

In March 2019 Google signed a memorandum of understanding with the Cuban telecom ETECSA for a peering agreement connecting their Internet networks. This deal will require an actual cable connection in the near future.126 It seemed to contradict the Trump administration policy that imposed a new round of sanctions against Cuba, strangling the country's economy and hurting ordinary Cuban people's lives. Google's venture in Cuba, however, was consistent with the goals of US policy: integration of the socialist economy into the global capitalist system through digital commerce. According to a 2019 report by the US State Department's Cuba Internet Task Force, it was recommended that Cuba's Internet infrastructure be improved by building a direct submarine cable between the United States and Cuba to promote unfettered Internet access.127 Google has been backed by over seventy-five years of US government “free flow of information” policy, which was also used against the New World Information and Communication Order movement in the 1970s as a weapon to force Cuba into the global capitalist economy.128

Another land mass at which Google has taken aim is Africa. Often seen as a little-connected continent, Africa is increasingly turning into a new battlefield among global Internet companies. Given that fewer than half of Africans are online, the continent is the region with the highest growth potential for Internet use in the world, and Internet firms see it as a land of opportunity and a massive potential market. Google's third private submarine cable, Equiano, is on its way, linking Portugal to South Africa with branches to St. Helena, Togo, Namibia, and Nigeria, the first African country where Google rolled out WiFi hotspots.129 This is Google's first cable to stretch from Europe to Africa, opening up the spigot of capital flow into Africa.

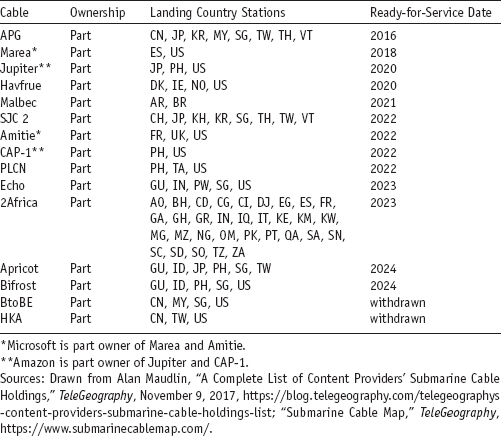

Facebook is not far behind Google. The company is part of a consortium composed of units of China Mobile Ltd., MTN Group Ltd. (South Africa), Orange SA (France), Saudi Telecom Co., Telecom Egypt, Vodafone Group PLC (United Kingdom), and WIOCC, which is owned by fourteen African telecom carriers. The consortium is constructing a megacable, 2Africa, originally called Simba, which stretches twenty-three thousand miles to cover the entire continent, with routes to Europe and the Middle East.130 According to a 2019 Telegeography report, Facebook was part of ten submarine cable projects in Asia, Europe, and Latin America.131 In Latin America, Facebook funded a twenty-five-hundred-kilometer submarine cable called Malbec connecting Buenos Aires, Argentina, with São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and stretching to the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre.132 The cable was built in partnership with a private company called GlobeNet, which is part of the Brazilian finance company BTG Pactual.

Table 2.2. Facebook submarine cable holdings

To cover the Atlantic Ocean, Facebook joined Microsoft and Telefonica's Telxius to build the MAREA cable, with termini at Virginia Beach, Virginia, and Bilbao, Spain. Both Facebook and Microsoft have cloud data centers located in Virginia, and these centers link to Bilbao, which is on a strategic path to network hubs in Africa and the Middle East. In Asia, Facebook is racing against Google, with five cables in the region: the Asia Pacific Gateway (APG), Bay to Bay Express (BtoBE), Southeast Asia-Japan Cable 2 (SJC2), Jupiter, and Hong Kong-Americans (HKA). Eventually, BtoBE and HKA were canceled due to US government pressure. These cables connect to Japan, Taiwan, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Malaysia, circling East and Southeast Asia. Amazon is also part of the BtoBE and Jupiter Cable System consortia, but separately Amazon invested in the consortium that built the Hawaiki Submarine Cable, which links Oregon, Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and American Samoa. The state of Oregon has a heavy concentration of submarine cable landing stations because of its geographical proximity to both Silicon Valley and Los Angeles and to the Pacific rim.133

These newly emerging submarine cables built by the large Internet firms are strategically laid around the major global nodes, linking data centers to data centers to entwine the global market. The size and capacity of these networks is almost compatible with tier one Internet backbone companies, so they are even able to exchange traffic without extra cost and more quickly deliver traffic close to their users. These companies’ hyper data centers and massive private backbones of terrestrial and submarine cables combine to form these firms’ cloud networks, which consist of points of presence (POP), edge nodes, content delivery network locations, and dedicated Internet locations.

According to Google, the company has over ninety Internet exchange points where Google's backbone connects with other network operators via peering.134 The company has more than seventy-five hundred edge nodes around the globe where Google caches its content on its servers, hosted in local ISPs, to speed up delivery of content and services.135 This is possible because Google has a backbone infrastructure large enough to allow network traffic exchange with other tier one network providers136 as well as the ability to leverage its heavy traffic with local ISPs where Google can cache its content in order to realize efficiencies of localized data in its network and servers. Google operates its Cloud Content Delivery Network, which has more than one hundred cache sites across major metropolitan areas to serve out services and applications more quickly and reduce costs.137 Amazon and Microsoft have organized themselves similarly. Amazon's infrastructure is made up of different geographical regions divided into availability zones. Amazon has a network of 190 points of presence and 179 edge locations in 72 cities across 33 countries,138 and Microsoft has 54 regions in 140 countries.139 These Internet companies not only own their backbone infrastructure but also operate and control the largest agglomeration of smaller infrastructures. They are building the privatized Internet.

Last Mile

Although building out their own network infrastructures for internal operations and data center connectivity is vital, it is also important for Internet firms to connect to end users for the consumer side of their business. Completing the last mile is the precondition for any consumer Internet business. Thus, Internet firms have been advocating for ultrafast fiber-optic networks to speed up the last mile using such PR façades as the “digital divide,” “equal access,” and the “digital revolution.” This seems outwardly to be an extremely thoughtful gesture, but these companies are actually motivated by corporate self-interest. The more access to high-speed Internet is available, the more Google is queried, the more YouTube videos are viewed, the more apps are used, the more Amazon orders are placed, and the more Facebook images are liked—all of which mean more revenue for these companies.

In 2010 Google ambitiously launched its Google Fiber project with the promise of providing free Internet access to consumers up to five Mbps, and one gigabit per second for $70 per month, which was one hundred times faster than the average US broadband service.140 Google first rolled out the service in Kansas City, Kansas, and Austin, Texas (heavily subsidized by the municipalities themselves, it must be noted) and subsequently in six other US cities.141 One of the reasons behind Google's venture was to spur the telecom and cable industries to improve their broadband offerings and enhance broadband speeds and penetration. All of this is necessary for Google to expand its wide-ranging services, which require fast and widespread broadband infrastructure to incentivize their adoption and use.

Seven years later Google abandoned the project because it realized that laying out actual pipes consumes enormous amounts of capital and has a slow rate of return. As the legal scholar Susan Crawford pointed out, last-mile access was a capital-intensive project requiring a long-term investment, but Google's shareholders weren't willing to wait; they wanted to see a return on investment sooner.142 Google fiber was also often delayed, since the company needed permission to access local utility poles that were already being used by incumbent telecom companies such as AT&T and Comcast. The former sued the city of Louisville for allowing Google to install its wires and temporarily move existing AT&T wires without prior consent to create space for new ones.143 This legal process was used by telecom companies to slow down the Google Fiber project. In August 2018 the FCC approved a rule known as One Touch Make Ready, allowing Google Fiber and other ISPs to install their wires on utility poles without waiting for incumbent telecom companies to move their wires. This was too late for Google because the company had already begun phasing out the project.

Google's entry into the realm of the telecom industry nonetheless fueled the broadband war. Google Fiber had been a direct challenge to such telecom giants as AT&T, Verizon, and Comcast, who had long battled over Internet services to generate more profit from their infrastructures. To a certain extent, Google's initial goal had been achieved because it pressured the incumbent telecom behemoths to invest more in their infrastructures to support high-speed Internet.144 Meanwhile, Google's retreat from its fiber project didn't mean that the last mile was no longer in the company's interest. Google was and is searching for alternative technologies for its last-mile connections and has pivoted its strategy to wireless broadband. In 2015 Google acquired Webpass (now called Google Fiber Webpass), a wireless home broadband company offering wireless Internet services in several metro areas. Google also experimented with millimeter wave technology, which uses the radio spectrum between 30 GHz and 300 GHz for 5G wireless Internet access.

Google continues on its quest for alternative last-mile technologies that don't require laying down capital-, labor-, and time-intensive fiber-optic cables. Meanwhile, instead of building its own network, Google decided to piggyback on unused networks of other mobile carriers such as like Sprint, and T-Mobile. Google operates its own mobile virtual network operator called Google Fi (nee Project Fi). Google Fi automatically configures and switches to the strongest mobile network and provides a low-cost wireless service while also avoiding competition with traditional phone companies.

Google's pursuit of last-mile connectivity goes well beyond the United States since the company is eager to capture the entire global population. In order to reach “the last billion,”145 Google has experimented with a range of Internet technologies in remote areas of the world where little affordable network infrastructure is available. In 2013 Google embarked on its Loon project, which worked on last-mile solutions to rural and remote areas of the world including Kenya, Peru, and Puerto Rico. The idea was to use high-altitude balloons to beam Internet signals into such regions. Google also signed a commercial deal with Telkom Kenya and established several ground stations in Nairobi and Nakuru. However, after almost ten years Google walked away from the project, not because there were no longer social needs but because it was “commercially not viable.” Although Google withdrew from Loon, its wholesale broadband infrastructure project, the Csquared urban network project is still operating in Uganda, Ghana, and Liberia with funding from ICT investment companies Convergence Partners, Mitsui, and the International Finance Corporation, which is part of the World Bank Group.